WOF (World Obesity Federation):

The World Obesity Federation takes the position that obesity is a chronic, relapsing, progressive disease process and emphasises the need for immediate action and the prevention and control of this global epidemic. 13

TOS (The Obesity Society):

It is the official position of The Obesity Society that obesity should be declared a disease. 10

AACE (American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists):

"[Obesity] must be viewed as a chronic disorder that essentially requires perpetual care, support, and follow-up." 11

CMA (Canadian Medical Association):

"It is important for health care providers to recognize obesity as a disease so preventive measures can be put in place..." 12

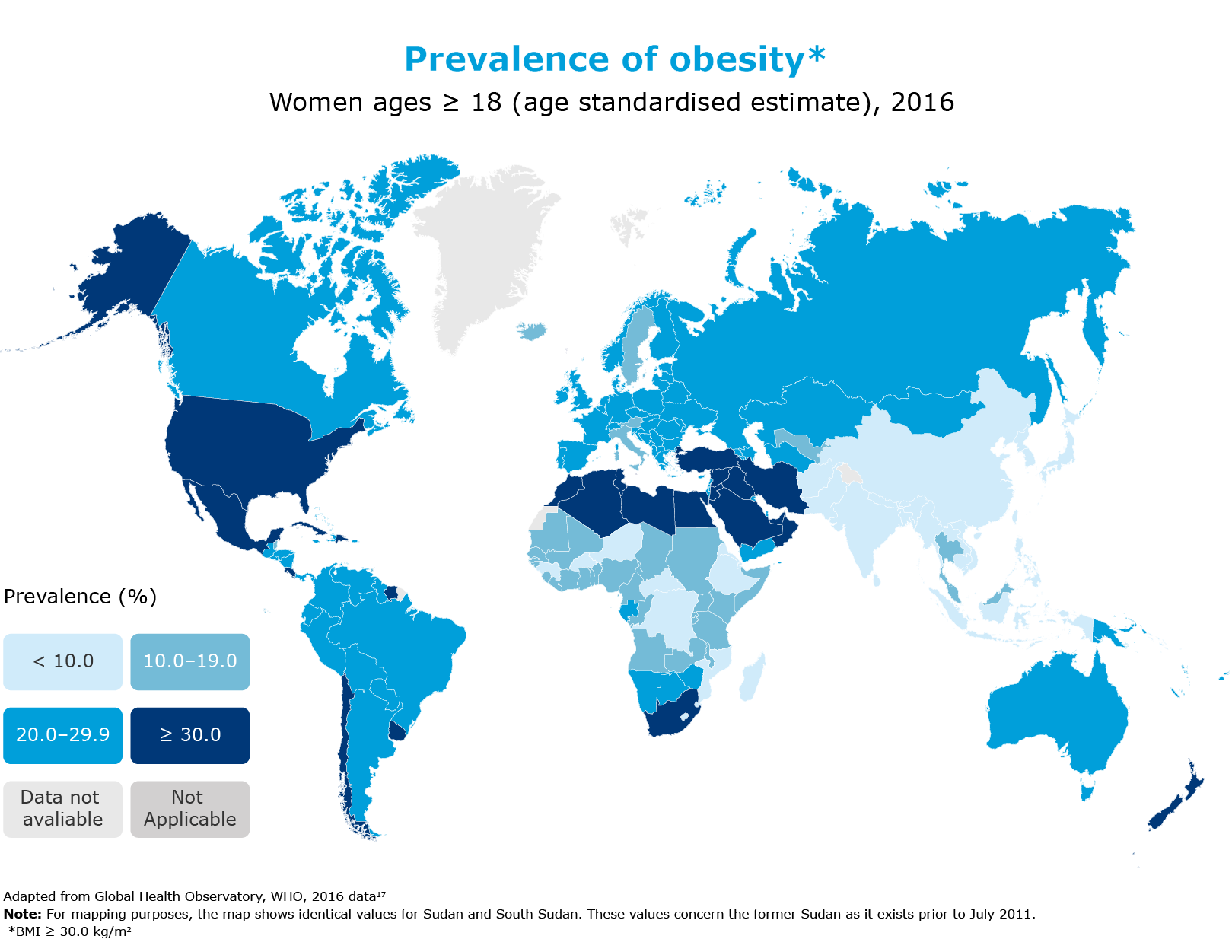

The global prevalence of obesity has nearly tripled since 1975. In 2016, more than 1.9 billion adults aged ≥ 18 were overweight. In the same year, 39% of adults aged ≥ 18 were living with overweight, and 13% were living with obesity.16

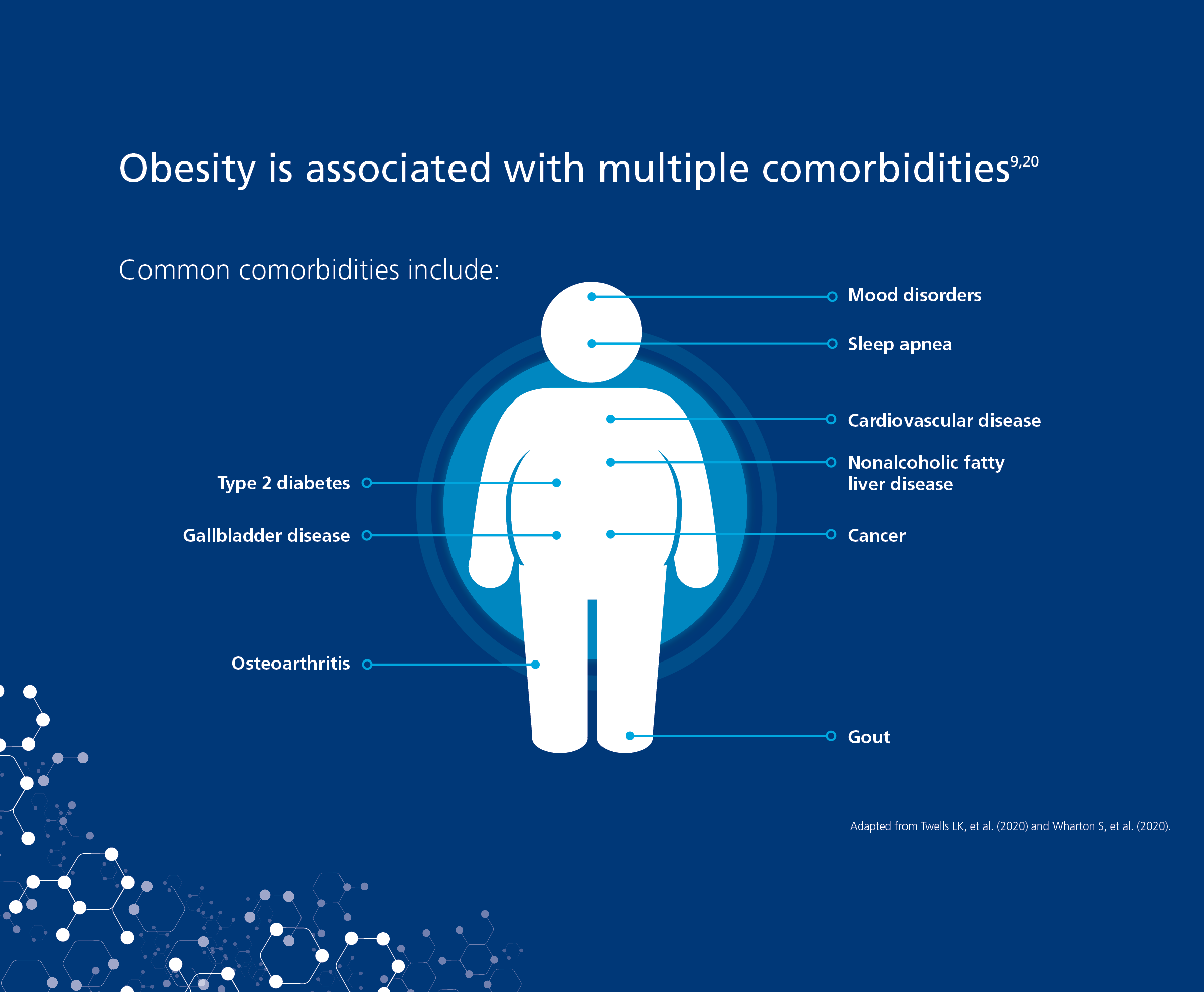

Canadians with obstructive sleep apnea are more likely to have diabetes, hypertension, heart disease and mood disorders.26

Obesity was also responsible for high costs associated with its comorbidities29

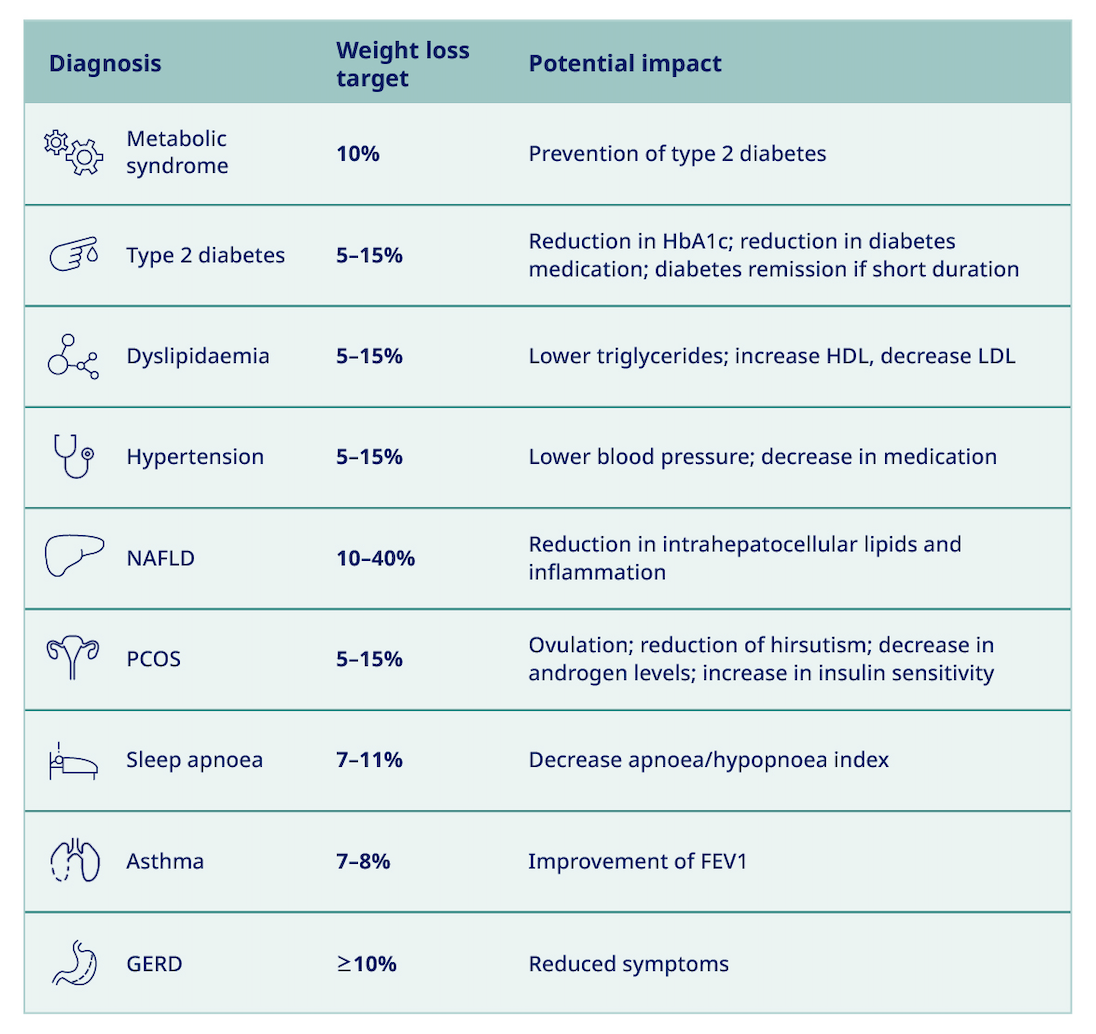

How could weight loss, achieved through behavioural treatment, impact patients with the following conditions?

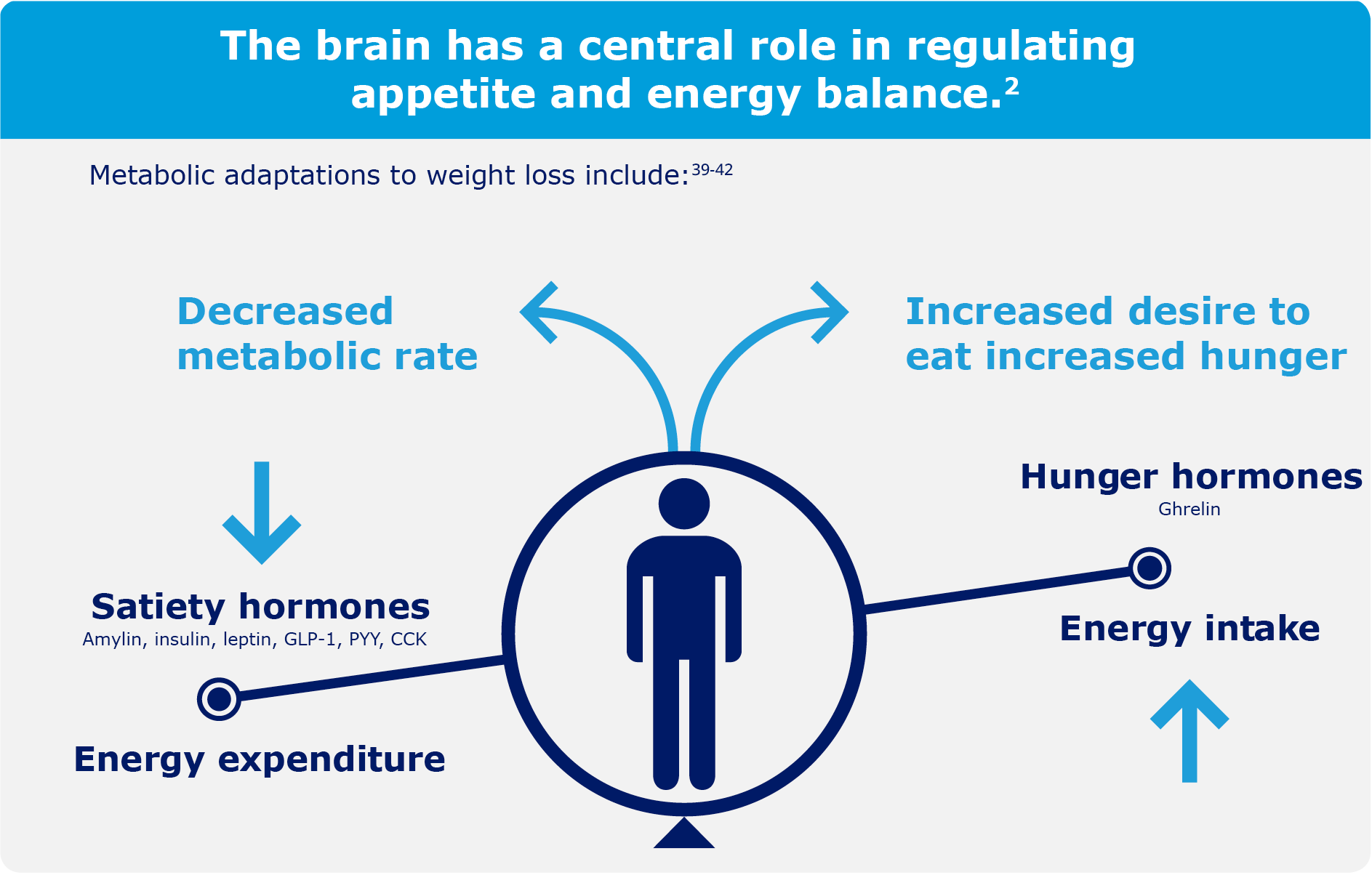

Science has discovered that physiological responses to weight loss trigger weight regain.

Weight loss in people living with obesity has been shown to cause changes in appetite hormones that increase hunger and the desire to eat for at least 1 year.39

Multiple hormones, such as ghrelin, GLP-1, and leptin, play an important role in regulating appetite.2

The ACTION (Awareness, Care and Treatment of Obesity MaNagement) Study is the first Canada-wide study that investigated the perceptions, attitudes, and perceived barriers to obesity management among Canadian people living with obesity (PwO), healthcare professionals (HCPs), and employers. The study was conducted through an online survey between August and October of 2017. The findings of this study highlight the misunderstanding and communication gaps that exist between these groups.44

The majority of the 2545 survey respondents* agreed with the statement that “obesity is a chronic medical condition”.44

74% of PwO reported that they believe obesity has a large impact on overall health.

81% of PwO agreed that it would be beneficial to their health to lose 5–10% of their body weight.

Selected outcomes of the ACTION Study can be grouped into the following topics:44

Obesity should be treated and managed holistically and as a serious chronic disease.11,47

Behavioural and lifestyle interventions:

For obesity, this should include diet, exercise, and behavioural modification.47 Medical nutrition therapy, physical activity, and health behaviour changes are first-line interventions in all individuals with a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 and they are recommended as the basis for all obesity management plans.48-50 However, behavioural interventions may not always be sufficient to maintain weight loss and some people living with obesity may require a combination of treatments that includes pharmacotherapy and/or bariatric surgery to help manage their weight.9,43,45

Pharmacotherapy:

For people living with obesity, pharmacotherapy should be considered as a treatment option to decrease weight and improve metabolic and/or health parameters when health behaviour change alone has been ineffective, insufficient, or without sustained benefit.

Based on guideline recommendations, pharmacotherapy can be used for:45

Patients with a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2 or ≥ 27 kg/m2 with adiposity-related complications, in combination with medical nutrition therapy, physical activity, and psychological interventions.

Patients with type 2 diabetes and a BMI > 27 kg/m2 for weight loss and glycemic control, in combination with health behaviour changes.

Patients with prediabetes and overweight or obesity (BMI > 27 kg/m2) to delay or prevent type 2 diabetes, in combination with health behaviour changes.

Bariatric surgery:

Bariatric surgery is an intervention for obesity management which is recommended in:51

Patients greater than 18 years of age with a BMI of 35 kg/m², who have at least one major obesity-related complication.

Patients with a BMI between 30–34.9 kg/m² who have been refractory to nonsurgical attempts at weight loss with obesity-related complications, especially type 2 diabetes.

Patients with a BMI ≥ 40 kg/m², independent of the presence of obesity-related complications.

Bariatric surgery requires lifelong medical monitoring and treatment of potential long-term nutritional deficiencies.51,52